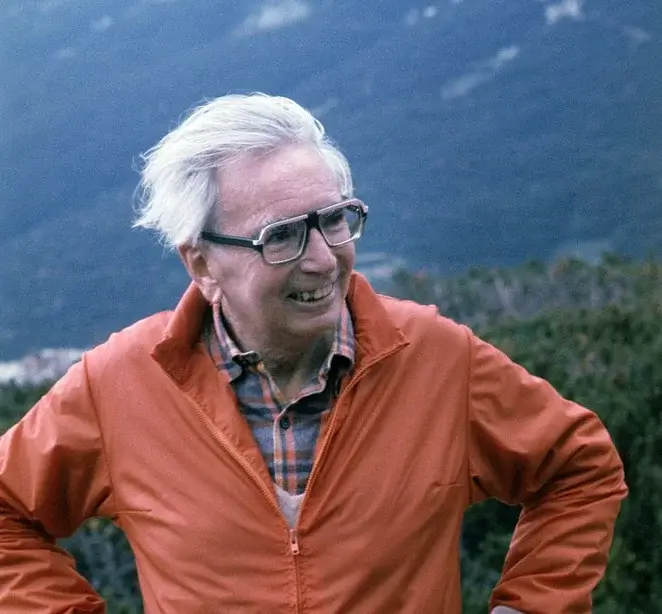

Last week, we marked what would have been Viktor Emil Frankl’s 120th birthday— work, life, and hardships of a man whose insights continues to redefine meaning, healing, human will and freedom.

He was many things—psychiatrist, Holocaust survivor, thinker, therapist, but to me something more personal. Sometimes I even feel a strange closeness to him, as if an old grandparental presence follows me. His experience speaks to something I carry in my own family history—stories of survival and loss during the Holocaust. Some of my relatives survived ghettos and camps; others didn’t make it out.

There are many books, and stories told about Holocaust, its victims and survivors. Still, for me, Viktor Frankl’s most famous book Man’ s Search for Meaning (1946) stands out from the rest because it is not only his personal story and subjective experience as a victim but an attempt to explore and examine those horrible events objectively as a researcher from within. It offered a way to imagine what my grandfather might have endured and, more importantly, what might have helped him carry on. It is a unique experience of a Man, that not only survived but helped others to remain alive and carry on through what Karl Jaspers called “boundary situations”. I’ll never know what specific meaning he held onto. But Frankl helped me believe that such meaning existed.

Psychotherapy with a Human Face

Born in Vienna in 1905, Frankl was deeply shaped by thinkers like Nietzsche, Freud, Adler, and Max Scheler, but his own life took a course no theory could prepare him for. He survived four concentration camps, while losing his parents, brother, and wife. Out of that devastation, he did something extraordinary: he did not turn away.

Instead, he looked directly into the abyss and asked: Can life still have meaning here? His answer was yes—and this became the foundation of logotherapy, or what he called psychotherapy with a human face.

Frankl believed that even in the face of pain, guilt, and death—what he called the tragic triad—we are still free to choose our response. He saw meaning as the central human motivation—not pleasure (Freud) or power (Adler), but meaning.

His Ways to Find Meaning

The man in his active life realises himself in creative work, in a sedentary life lets him experience the enjoyment of art and nature. However, existence is restricted by external forces where man is deprived of creativity and enjoyment. Suffering and death give life wholeness.

Frankl identified three pathways to meaning or “Hauptstraßen zum Sinn” (main roads to meaning).

Creative values – through work, art, and contribution.

Experiential values – through love, beauty, and connection with nature.

Attitudinal values – through the way we respond to unavoidable suffering.

This final one—attitude values— resonates most with me. Even in situations beyond our control, we have the freedom of choice how to react. With a brave or hopeful attitude, individuals can find meaning even within suffering. If we can’t change the situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.

Frankl wrote, “When a man finds that it is his destiny to suffer, he will have to accept his suffering as his task; his single and unique task. He will have to acknowledge the fact that even in suffering, he is unique “and alone in the universe. No one can relieve him of his suffering or suffer in his place. His unique opportunity lies in the way in which he bears his burden.”

According to him, not only do suffering and death have meaning, but if there is meaning in life at all, then suffering must be included in that meaning.

Even in the darkest conditions, when nothing can be done, we can still find meaning in how we bear what must be borne. This is not about glorifying suffering—but about not letting it hollow us out.

Meaning as Resistance

Frankl’s approach wasn’t passive. He was directive when needed, even paradoxical. He often asked patients to live as if they were doing so for the second time—this time, choosing more wisely. He used techniques like paradoxical intention (asking a client to exaggerate their feared symptom) and dereflection (shifting attention from problems to meaning). He also believed in the power of spiritual stubbornness—a refusal to let suffering strip us of our dignity.

He was sometimes criticised for not focusing more explicitly on his Jewish identity in his writing. His response: he did not want to capitalise on being a Jew. Instead, he wrote from a universal human perspective, choosing meaning over identity politics.

What Frankl Taught Me

I first encountered Frankl during my early psychology studies—his name, his theories, his presence on the page. But it wasn’t until years later, in a much harder season of my life, that Man’s Search for Meaning truly reached me. I didn’t just read it—I leaned on it. And it held.

What struck me wasn’t only the scale of what he endured, but the quality of his response. The clarity. The steadiness. The refusal to let outer devastation dictate the state of his inner world. He showed me that even when everything is stripped away—home, family, freedom, future—we still retain the freedom to choose our attitude. We are still responsible for how we carry what remains.

That belief strengthened me in quiet but lasting ways. It gave shape to something I couldn’t quite name at the time: a kind of dignity not based on outcomes, but on presence.

Goethe once said, “If we take a man as he is, we make him worse. But if we take him as he should be, we make him capable of becoming what he can be.”

Frankl lived this. He saw not only who people were, but who they could become, even in the ruins. His perspective informs my own, and even when I am disappointed and resentful, I try to believe – in others and, perhaps more hesitantly, in myself.

Suffering and Completion

Frankl argued that suffering and death don’t negate life—they complete it. Just as day needs night, summer needs winter, life needs boundaries to be fully lived.

He wrote:

“Suffering ceases to be suffering at the moment it finds a meaning, such as the meaning of a sacrifice.”

Even in the most difficult of all perhaps difficult situations, in which one no longer can be expressed in any sort of act, in which only suffering stands as the very last recourse – then is one able to reconstruct himself with recreation and recollection upon the vision of his dearest. Suffering finds its triumph with a success inside.

Even when stripped of freedom, home, family, and future, a person can still choose. Choose to remember a loved one. Choose to endure with dignity. Choose to keep walking.

Carrying It Forward

No, I’ve never experienced what Frankl did. But like everyone, I’ve had dark moments, and I know the ache of asking “what now?” In those moments, Frankl’s question echoes in me: What does life expect from me now?

That question pulls me forward. It connects me to others. It gives me responsibility—for my family, my work, my choices. It keeps me from falling into apathy.

He reminds us that meaning is always there—not given, but waiting to be made.

Final Thought

Frankl’s teachings remind me that the inner life is not passive. We are not at the mercy of our circumstances. Our freedom lies in our response, in how we hold ourselves, and others, through darkness.

I believe that internally and spiritually, a person can be stronger than his external circumstances. Man always and everywhere is facing obstacles and opposes fate, and this opposition allows him to turn his suffering into an inner achievement.

Our life is unique and unrepeatable. It is in constant flux . There is a day, and there is a night. There is a summer, and there is a winter. There are bad times and good times. Therefore I know that there is no constant dark times. Yes, they can last long, but there will be a sunrise one day.

Celebrating his 120th birthday, I hold that thought close. I choose to believe in people. In meaning. In the quiet strength that comes from choosing who we become, even when the world seems unbearable.