A few months back, I found myself in Yorkshire on a personal matter and, by chance, passed through the area where Netflix’s Adolescence had been filmed. That moment caught me between the ordinariness of the place, the weight of what had been captured there on screen, and my own practical experience. The area looked smaller than it had appeared in the one-shot crime drama, filmed almost entirely at Production Park, a rehearsal and filming space that has hosted some of the world’s biggest stars and touring artists. However, the story of Adolescence and my own reflections on what it means to be suspended between childhood and whatever comes after, came to the fore, overshadowing the technicalities of production and filmmaking.

There’s something about working with teenagers that continues to unsettle me in the most necessary ways. They are always in flux and refuse to fit into the neat boxes adults prefer: neither the protected vulnerability of childhood nor the assumed solidity of adulthood, but something altogether more precarious, and perhaps more honest about the human condition than we care to admit.

The creators of Adolescence understood this, I think. This four-part series follows 13-year-old Jamie Miller, arrested for murdering a schoolmate, with each episode shot in one continuous take. It shows how the relational world becomes both sanctuary and battleground during these years, how every interaction carries the weight of identity formation, how social media doesn’t merely amplify teenage drama but fundamentally alters the texture of becoming itself.

The show highlights how the manosphere has influenced adolescent boys, with characters directly naming Andrew Tate and the “red pill” community. In one key scene, Adam, the teenage son of Detective Inspector Luke Bascombe, tries to explain to his father what’s really happening online: “You’re not reading what they’re doing. It’s a call to action by the manosphere.” His father is used to threats he can see and understand; Adam is pointing to something more elusive: coded language, online influencers, and ideological recruitment that most adults never detect.

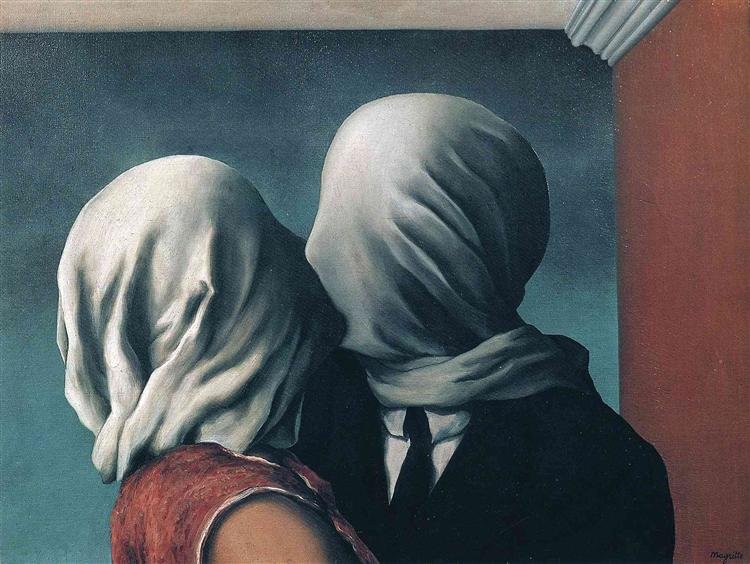

It’s a stark reminder of what philosopher Martin Heidegger called our basic condition of “being-with-others” — the fact that we are never truly alone, but always existing alongside other people, shaped by their presence, their gaze, and their judgment. Heidegger also warned that technology shapes how we see the world and ourselves, a process he called “enframing”: the tendency to treat people and experiences as resources to be organised and optimised.

He could not have anticipated Instagram or incel culture, but the truth he identified still holds. We are always in relationship, always vulnerable to how others see us. In Adolescence, this digital enframing transforms teenage relationship-building into something unrecognisable from previous generations — friendships and identities mediated through performance, metrics, and the constant potential for exposure.

This technological enframing poses particular dangers during adolescence. When everything — including the self — is treated as a resource to be optimised, teenagers lose access to slower, more authentic ways of being in the world. Their complex relational exploration gets flattened into profiles and posts; their vulnerability becomes public exposure; their uncertainty becomes something to be erased through instant digital validation.

The series became the most watched streaming show in the UK in a single week, garnering 96.7 million views in its first three weeks. Perhaps because it captured something we recognise but rarely acknowledge: the way teenage crises unfold in real time, without convenient commercial breaks or neatly resolved endings. Prime Minister Keir Starmer backed calls for the show to be screened in schools, writing, “As a father, watching Adolescence with my teenage son and daughter hit home hard.”

What strikes me, both as someone who survived my own turbulent adolescence and as someone who works occasionally with young people in therapy and workshops, is how desperately we adults rush to solve, to fix, to provide answers to questions that may not yet exist. There’s something almost violent in our helpfulness sometimes – an urge to strip away the ambiguity adolescence needs, reducing it to manageable problems with clear solutions.

As youth worker Misha Frank (Faye Marsay) says in Adolescence, “All kids really need is one thing that makes them feel okay about themselves.” It’s a deceptively simple truth and that “one thing” is rarely a neat solution we hand them.

Over the years, I’ve learned something that continues to challenge my therapeutic instincts: sometimes the most profound help comes from refusing to help. To hold back and to let their questions live a little longer before we try to answer them.

Sometimes the best way to begin is actually by not interfering – by not being instrumental and resisting the impulse to ‘enframe’ their experience into manageable problems with technological fixes. Instead, it’s about being there for them: creating room for them to breathe, staying steady, and showing you can remain present with them through whatever comes. That’s the main message we should convey: not efficiency, but presence in the face of their anxiety and uncertainty, and our willingness to sit with theirs. It’s the space to be fragile and fierce, to contradict themselves from one moment to the next, to grow at a pace that may even bewilder them.

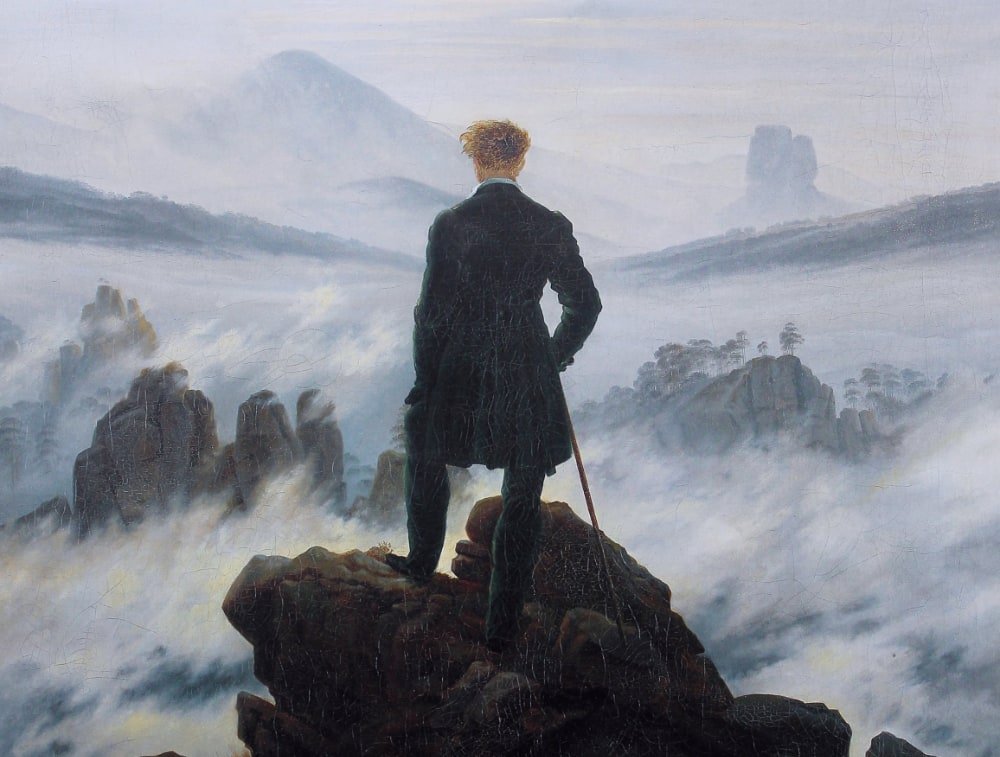

Standing near the filming locations: the Miller family home, the school, and the park where the fictional murder took place, I was thinking that the work, whether as parent, therapist, or simply as an adult who remembers, is less about knowing what to do and more about learning how to be.

To hold space for the becoming without trying to direct it.

To offer safety without removing the necessary risks of growth.

The fine line between abandonment and control, between trusting the process and honouring our responsibility to care – this is where the real work lives. In the space between knowing and not knowing, between helping and simply being present.

It’s uncomfortable territory. But then again, so is adolescence. So is being human in an age of uncertainty, when humanity itself risks becoming just another resource to be optimised.

This is where I start, at least. Where I started with my own children. Not with answers, but with the willingness and readiness to sit with the questions that may have no resolution.