The lone figure standing on the edge of a rocky cliff gazing into a vast, hazy landscape, in Caspar David Friedrich’s painting Wanderer above the Sea of Fog captures the uncertain place we find ourselves when we start to question the meaning of our own existence and our purpose in life. The swirling mist seems to evoke the anxieties and dilemmas, that cloud our path, while the higher vantage point stands for our capacity to see beyond the familiar. For me this is one of the eloquent metaphors of the existential approach: a courageous stance in front of the unknown, with the promise that something meaningful lies beneath the fog. It invites us to pause and take in that view— a reflection on how our sense of self, our choices, to clarify who we are and how we wish to live.

Easing Distress and Exploring Deeper Questions

The existential perspective often reaches individuals feeling weighed down by pain or in the midst of crisis. The overall goal is to soothe their hurt and help them grapple with unavoidable life challenges in a manner that fosters authenticity and satisfaction. Some existential therapists focus more directly on specific symptoms or problems, whereas others engage in a far-reaching conversation about what being alive truly involves, without strict targets or measurable results.

Rather than trying to “fix” a person, existential therapy strives to help individuals handle life’s fundamental dilemmas in a manner that fosters freedom, honesty, and a greater sense of wholeness. In other words, it is as much about discovering or rediscovering one’s sense of direction as it is about alleviating hurt.

Shared Responsibility and Honest Reflection

A significant component of this approach is asking important questions about why we exist and how we choose to live. It’s a collaborative effort: both parties freely discuss questions like “Why am I here?” and “How do my choices matter?”. Both the therapist and the person seeking help take part in this effort, looking closely at how we occupy our surroundings and how our actions can carry genuine consequences – whether in our own daily lives or in our ties with others.

Therapists working in this tradition often avoid using the term “patient,” choosing “client” instead. The shift in wording reflects the idea that this is not a strictly medical relationship. It is a candid encounter in which the client’s experiences, uncertainties, and hopes are examined with respect. Although symptom relief and behavioural changes can certainly occur, the deeper priority involves genuine reflection on what it means to be human.

Emphasising the Human Relationship

Existential therapy puts the bond between counsellor and client at the forefront. It invites a close look at the individual’s relationships with the broader world, not just in the session itself. At its foundation, it spotlights the inherently human condition and views every human event as tied to basic concerns about how we spend our finite time on this planet.

A Focus on Choices, Contradictions, and Possibilities

This mode of counselling examines how people make decisions, form personal identities, and maintain a particular way of being alive. It acknowledges the shifting, sometimes puzzling nature of human experience, and it inspires a genuine curiosity about what it actually means to be a person. In the end, it covers all the fundamental questions, such as who we are, what gives our lives a sense of purpose, how we deal with mortality, and how we choose to interact with freedom and responsibility.

The Origins of Existential Therapy

People have been contemplating human existence from ancient times, as evidenced by Greek philosophy. Old stories, such as those found in Greek mythology or biblical books, frequently provided moral lessons for dealing with life’s major concerns. Early Greek intellectuals, who valued intelligence, arranged these concerns in methodical ways, aiming to find answers for our role in this huge world that went beyond supernatural stories.

The modern form of existential therapy took shape in the 19th century, guided by philosophers who fixated on the essence of human reality. Thousands years later Søren Kierkegaard and Friedrich Nietzsche loom large in its ancestry, with both of them wrestling with life’s deeper puzzles. Kierkegaard believed that tapping into our inner awareness held the key to moving past our everyday discomfort, while Nietzsche spoke forcefully about personal freedom and the idea that we must own our actions. As the 20th century rolled around, other thinkers like Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Heidegger dove into these concepts further, insisting that existence itself precedes any definition of who we are. We show up in the world first; after that, we sketch out who we become through our interactions.

Before long, other influential minds such as Martin Buber, Karl Jaspers, Simone de Beauvoir, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and many more stressed the vital importance of personal experience in achieving a healthy state of mind. They recognized that no one can truly separate their being from the living environment or from the questions that keep them up at night.

Early Psychiatric Influences

In the early 20th century, existential thinking started weaving into psychiatric care, often credited to Karl Jaspers’ philosophical vision and the psychiatric work of Ludwig Binswanger, Medard Boss, and Viktor Frankl. Frankl’s idea of “logotherapy” was born out of his experiences in caring for those who felt suicidal and his own ordeal surviving concentration camps during World War II. He noticed that while some people abandoned all hope, others discovered a deeper reason to survive.

Meanwhile, Jaspers left behind his psychiatry training and went on to ponder philosophical ideas, while Boss and Binswanger found themselves searching for different ways to handle emotional and mental struggles by examining their patients’ paradoxes head-on. During the 1960s and 1970s, the psychiatrist R.D. Laing built communities in the UK that offered alternative living arrangements for individuals struggling with emotional well-being. Around the same time, Paul Tillich (a German existential theologian), along with psychologists Rollo May and Irvin Yalom, gave this approach a firmer foothold in the United States. Yalom suggested four key issues—death, isolation, meaninglessness, and freedom—that stand in the way of a satisfying life.

Our Ever-Shifting Nature

A central idea in this philosophy and therapeutic approach is that as humans, we are always in motion, capable of reflection, and able to reinvent ourselves moment by moment. We are neither static nor trapped in old ways if we consciously decide otherwise. We’re capable of reflecting, reinventing ourselves, and adjusting to life’s twists and turns. Life itself forms our foundation, granting us the option to adjust and grow in response to what unfolds around us.

When we resist looking at our own freedom and possibility—perhaps because it feels too scary or daunting—this tension may emerge as emotional turmoil or discontent.

Interestingly, what some clinical models label “defence mechanisms” or “neurotic behaviours,” existential therapists may see as understandable attempts to dodge the anxiety that comes from confronting life’s uncertainties. The goal in existential work is to recognise these patterns, examine them for their roots and meaning, and then decide if they serve us or hold us back.

Phenomenology and Core Concerns

Existential therapy rests on ideas borrowed from phenomenological and existential philosophies, which revolve around profound personal freedom, the need to find meaning, and the challenging realities of evil, separation, anguish, guilt, anxiety, hopelessness, and loss. In these sessions, phenomenology is used as a way of looking closely at someone’s subjective reality. The therapist temporarily sets aside preconceived notions by “bracketing” one’s own assumptions to gain a clearer picture of how another person experiences the flow of living.

In practice, phenomenological awareness involves the therapist:

1. Temporarily setting aside personal biases, theories, or clinical labels.

2. Focusing on how the client feels in the moment and experiences the therapist’s presence.

3. Describing these observations rather than jumping to interpretations.

This descriptive stance recognises that therapy is not something done *to* the client, but rather something created *with* the client. The interactions and revelations that unfold are, in a real sense, co-constructed.

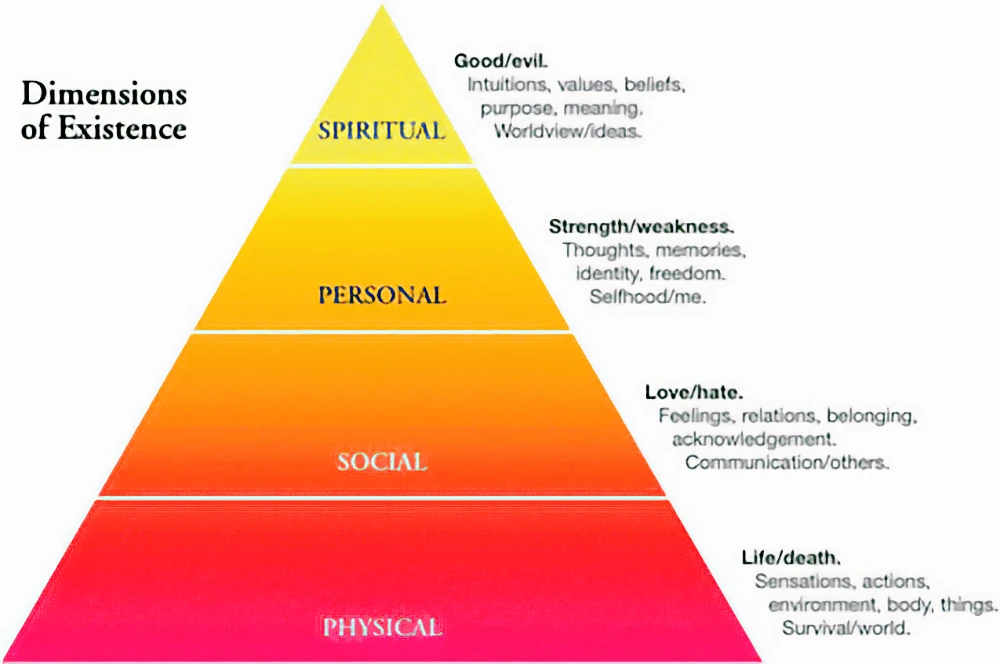

The Four Dimensions of Existence

One of the key roadmaps and practical insights in existential therapy comes from Ludwig Binswanger’s view of our main realms of existing, with a later addition by Emmy van Deurzen-Smith. We can picture these dimensions as intersecting circles. Each sphere shapes how we interpret events and connect with others.

Umwelt (Physical Sphere)

This is about the natural setting in which we live—our bodies, our surroundings, and the influence of nature. Someone might feel completely at ease with a gentle breeze and the steady rhythm of daily routine, while another person might experience persistent concern about health or safety. In existential therapy, these reactions matter because they reveal how we interpret whatever the physical environment offers.

Mitwelt (Social Sphere)

This includes everything related to relationships, culture, community, and interactions with friends, family, and strangers on the street. Some might sense belonging and acceptance here; others feel alienation or worry. We look closely at these dynamics because they can inform deeper beliefs about trust, respect, or emotional distance.

Eigenwelt (Personal Sphere)

Here, we explore the way we perceive ourselves—our self-esteem, emotional security, and our own definition of who we are. It also covers the close bonds we share with those who mean the most to us. These intimate connections can offer a sense of purpose or, alternatively, create uneasy emotions. Getting to the heart of how we view ourselves is a major step.

Überwelt (Spiritual or Ideological Sphere)

Van Deurzen added this category to account for the ideals and broad beliefs about matters like life, mortality, or one’s guiding moral code. It might or might not involve religious faith. The main idea is that these beliefs shape how we handle distress, contentment, and everything else in between.

By stepping through these four angles on living, therapist and client can shine a light on subtle biases, hopes, and anxieties. It’s a chance to re-evaluate what we’ve always assumed and see how that might contribute to life’s challenges.

Facing an Existential Crisis

People often seek this approach when they find themselves confronted by existential hurdles—moments when fundamental aspects of survival, identity, or personal importance feel threatened. Such fears might be physical, relational, emotional, or spiritual, and they may target us or our communities, or even the beliefs we hold dear. Because we are in constant transition, it’s natural to be hit by these crises at various points in life. In existential therapy, these jarring periods are seen as both worrisome and full of possibility. They can be moments when we shake off old patterns and discover new perspectives.

How the Process Unfolds

In existential therapy, the counsellor and client join forces to have an honest, probing conversation. The therapist brings professional expertise, while the client brings the details of their own situation, acknowledging the client’s worldview as something that can’t be shoehorned into a simple diagnosis. A caring, open, and often challenging connection between the two is considered essential. This bond shapes the success of the work done together.

Painful experiences are viewed not as “defects” to be quickly removed but as gateways to self-discovery. In time, clients may unravel persistent themes, see them for what they are, and decide how they want to respond from this point on. Existential therapists strive to remain genuine partners in this exploration: challenging, reflecting, and encouraging clients to confront paradoxes or inconsistencies, but never seeking to impose their own values.

Tying Together the Past, Present, and Future

Practitioners in this style look closely at what people feel in the current moment, how they interpret events, and how they connect with others. These observations can illuminate how past experiences have carried over into everyday routines and can also shine a light on emerging possibilities. By mixing empathy, a down-to-earth attitude, and patient listening, therapists strive to gain a wide picture of a person’s way of relating to life.

Rather than scrambling to escape or reduce our struggles, existential therapy encourages us to view them as windows into greater self-awareness. Our hardships can act like riddles, nudging us to look more deeply into who we are and what we truly value. When approached with an open mind, these difficulties can offer insights about our place in this grand puzzle we call life.

Confronting Contradictions

Counsellors in the existential approach are usually careful about pushing personal opinions onto clients. However, they may highlight inconsistencies or paradoxes in a person’s behaviour. These are universal tensions within principles and values that tied closely to our identity and need for stability. They often highlight the struggle between opposing forces—love and hate, joy and sorrow, closeness and distance—that define human existence.

In some cases, therapists might challenge destructive habits, while in other cases, they steer clear of labelling thoughts or emotions as either good or bad. The goal, in its deepest sense, is for individuals to see their hardships in a wide context, then harness their own freedom and accountability to modify those struggles—or, in certain situations, come to terms with them. This might include discovering how to endure, affirm, or fully accept one’s chosen way of living.

Existential therapy strives to strengthen a person’s awareness of their inner life: the steady stream of observations, feelings, and reflections that happen moment to moment. While it respects the impact of earlier experiences and future concerns, it shines particular attention on how they shape the here and now.

How Is It Different from Other Approaches?

Existential therapy stands apart by focusing on the direct connection between therapist and client, the immediate lived experience, and the philosophical side of being alive. It isn’t as centred on diagnosing disorders or making symptoms disappear quickly. Rather, concerns like anxiety or deep sadness are seen as meaningful reactions to someone’s circumstances and personal history. The aim is to explore these states without simply trying to erase or ignore them. This style is more inquisitive than goal-driven and is more about describing and understanding anguish than about curing it outright.

Helpful Strategies

Though existential therapy generally does not depend on set techniques, many practitioners lean on a phenomenon-based approach that calls for being fully present with the person who seeks help. Skills such as empathetic listening and thoughtful questioning often come into play. Some existential therapists also incorporate ideas from other forms of counselling—like psychodynamic or cognitive-behavioral—to craft a unique plan for each individual. But the main objective is to help a person gain clarity about their immediate experience within the broader framework of their life.

Main Aims

Above all, existential therapy tries to help individuals honestly and openly explore how they live. Together with the counsellor, they can clarify what their experiences mean at a deeper level. That may lead a person to consider weighty concerns like beliefs, mortality, freedom, and daily stressors. When done wholeheartedly, this deep dive into personal reality can inspire a shift: the decision to own one’s ways of being and choose paths that foster true fulfilment, significance, and honesty with oneself.

Who Might Find This Useful?

This way of working can resonate with a broad array of people, whether they are wrestling with a particular problem or simply seeking greater purpose. It can be practiced one-on-one or in settings involving children, older adults, couples, families, or groups. It also adapts well to different environments—private offices, community centres, medical clinics, or even corporate spaces. While it may not offer immediate solutions for acute psychiatric situations, it can blend effectively with medication or other forms of help to address more pressing concerns. For anyone drawn to exploring life’s larger questions, existential therapy has much to offer.

Looking at the Evidence

Studies indicate that some variations of existential therapy can boost well-being and deepen one’s sense of significance, with new research showing that the benefits often rival more conventional treatments. This lines up with what experts have known for decades: most therapeutic approaches can be effective, and picking the right one depends a lot on each person’s temperament, preferences, and circumstances. One especially vital ingredient is the warm, respectful, and empathic rapport between therapist and client. Another key factor is the search for meaning—something existential therapy treats as a central focus in healing.

References

Deurzen-Smith, E. van (1988). Existential counselling in practice. London: Sage

Frankl, V. (1963). Man’s Search for Meaning. Beacon Press.

Spinelli, E. (2006). Demystifying therapy. Ross-on-Wye: PCCS Books.

Vos, J., Craig, M., & Cooper, M. (2015). Existential therapies: A meta-analysis of their effects on psychological outcomes.

May, R. (1969). Existence. Basic Books.

Wampold, B. E. (2015). How important are the common factors in psychotherapy?

Yalom, I. (1980). Existential Psychotherapy. Basic Books.