Why “the special feeling” doesn’t hold a relationship -and what tends to, instead

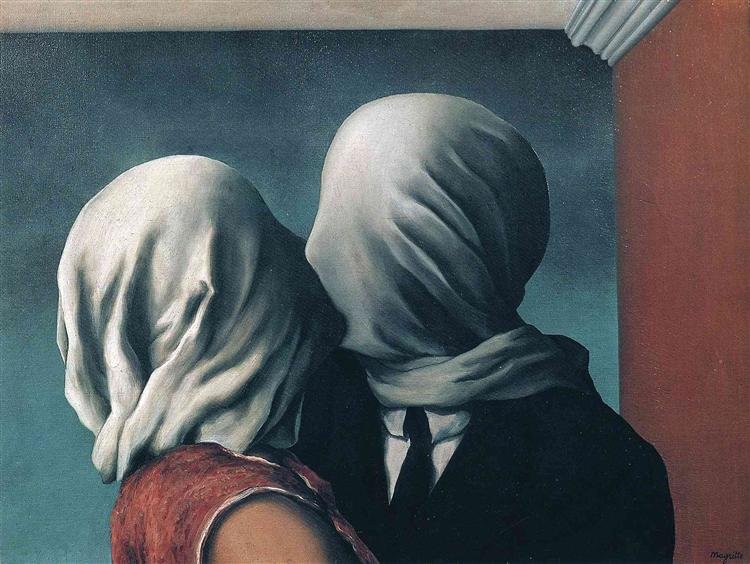

There is a phrase attributed to the Yanomami (an Indigenous people of the Amazon) that I keep returning to because it names something we usually romanticise rather than recognise: Ya pihi irakema — “I’ve been contaminated by your being.”

It is blunt. It is unsentimental. And it captures what love actually does when it’s real: it alters you. Not as a promise. Not as a performance. As a fact.

And yet, after the contamination, the vows, the photos, the language of “forever,” a large portion of relationships still end.

So what fails?

In clinical work, I rarely see love “disappear” in a clean way. More often, what collapses is the structure people have built around love — the expectations, the implicit contracts, the mythology. The feeling may have been genuine. The framework was not built to carry a life.

The romantic myth

Romanticism gave us soulmates, destiny, and the promise that the right person would complete us and make loneliness evaporate. Historically, this is quite new: Romanticism as a cultural movement which is barely 250 years old and for most of human history, partnership was primarily pragmatic: survival, land, lineage, child‑rearing.

The modern story is prettier. It is also more brittle.

Because the myth asks us to trust one thing above everything else: instinct. That “special feeling.” And instinct can be wise, but it is not automatically trustworthy. Sometimes it’s not wisdom. Sometimes it’s conditioning.

Familiarity isn’t compatibility

One of the uncomfortable things you learn from attachment theory (and from watching real couples over time) is this: we don’t reliably choose what will make us well. We often choose what feels familiar.

Familiar can look like chemistry: recognition, inevitability, destiny. But it can also be an old relational template returning in a new body—emotional distance that activates pursuit; unpredictability that keeps you vigilant; warmth paired with withdrawal so you learn to work for crumbs.

So that electric “this is it” feeling isn’t necessarily a compass pointing toward safety or suitability. It may be a mirror -reflecting the shape of what you learned early, including what hurt.

This is not meant as cynicism. It’s meant as leverage.

Because once a person can name their pattern, they’re no longer compelled by it. They can begin to choose rather than repeat. And that shift — from being driven to being aware is often where something like mature love starts.

Better questions than “Do I feel it?”

The Gottman Institute’s research is useful here because it pays attention to couples after the honeymoon glow, when the real material of life shows up: stress, fatigue, resentment, repair. What tends to matter is less poetic than we want and more actionable.

Three questions cut through the romantic fog:

1) Would you genuinely be friends with this person without attraction and plans?

Not “Do I want them?” but: on an ordinary Tuesday, would I choose their company? Their mind. Their presence. Their silence.

2) Do I respect how they are when I’m not the audience?

How they treat people who can’t give them anything back. How they handle power. Whether their values hold when no one is watching.

3) Can I accept what is unlikely to change?

Not tolerate. Not secretly bargain. Accept. The mess. The rigidity. The need for space. The temperament. The way conflict lands in their nervous system. If this stays, can I still choose them?

These aren’t romantic questions. They’re relational questions. They move you from feeling to seeing from projection to recognition.

The question we avoid

In practice, there is often a fourth question underneath all of this, and it rarely appears on a date:

What are my relational patterns, and how do they show up when intimacy gets real?

Or plainly: How do I become difficult to love?

This isn’t a moral judgement. It’s a doorway into self-knowledge.

We all have defences. We withdraw, we pursue, we control, we collapse, we intellectualise, we charm, we go silent, we demand certainty. Most of these strategies began as adaptations — ways to survive in early relationships. The trouble is that what protected us then often distorts closeness now.

The romantic fantasy suggests that the right partner will neutralise these patterns. The clinical reality is harsher and more hopeful: the patterns will show up, and the work is learning to recognise them together before they harden into contempt.

That is one definition of relational courage.

The triangle that holds

Robert Sternberg’s triangular theory of love gives language to something couples often feel but can’t map. He describes love as three interacting elements:

- Intimacy: closeness, trust, emotional bondedness

- Passion: desire, attraction, romantic energy

- Commitment: the decision to remain, build, and choose shared meaning over time

Early love often runs on passion. Over time, if things go well, intimacy grows. But commitment not as a vague promise, but as a repeated practice is what holds the structure when passion ebbs and intimacy is strained.

Many relationships don’t fail because love was “fake.” They fail because one corner of the triangle weakens and people interpret that shift as proof the relationship is over, rather than as information about what needs attention.

The couple as a third entity

Existential therapy starts from a simple premise: we are not isolated selves who later “add” relationships. We are shaped by relationship. And when I meet couple it is not merely two individuals side by side — it is a co-created system.

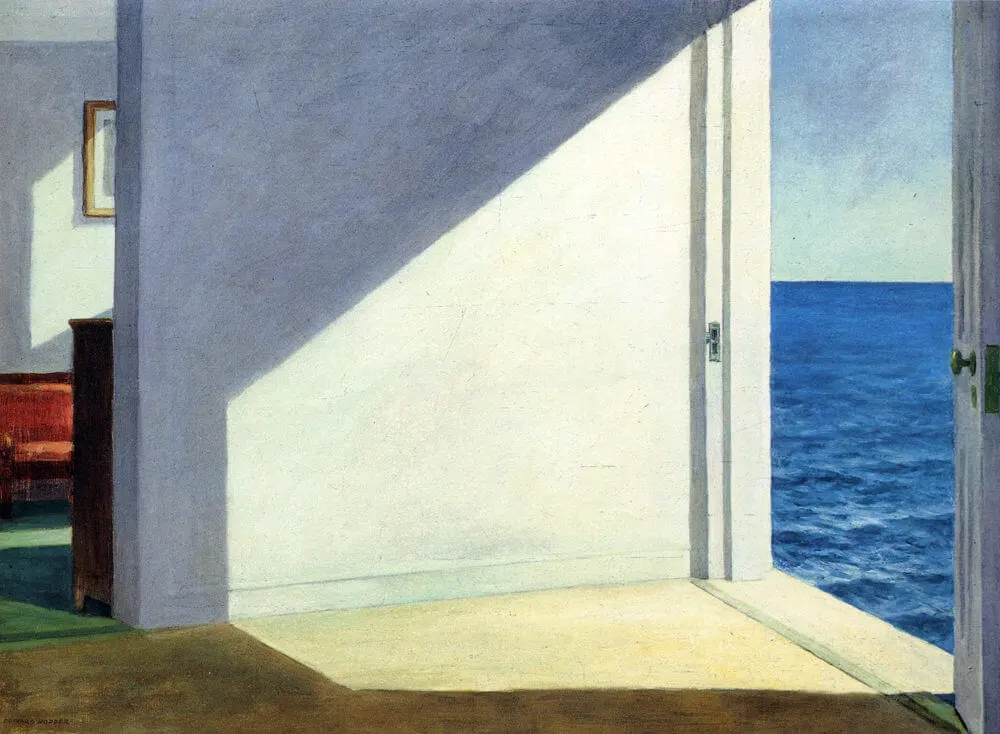

I often think of the couple-construct as a third entity living between two people: a shared field of meaning, assumptions, roles, fears, and rituals. It has its own history. Its own rules (often unspoken). Its own way of organising reality.

A lot of therapeutic work is making that invisible architecture visible:

- the roles that were assigned rather than chosen

- the resentments that became habits

- the “agreements” nobody remembers making

When couples can look at the construct -instead of only blaming each other -the conversation often shifts from “you always / you never” toward something more useful: what have we built between us, and is it still serving who we want to be?

What love asks, practically

If Romanticism tells us love is a feeling to be found, an existential view is less comforting and more durable: love is a stance to be taken.

That stance shows up in small, unglamorous choices: how you interpret your partner on a difficult day, whether you assume malice or strain, whether you can stay present without rehearsing your defence. Often the most loving move is not grand affection, but generosity of interpretation -assuming good intent when your nervous system is inviting you to assume the worst.

Paul Tillich described love’s work through listening, giving, and forgiving. The sequence matters. Listening is not passive. In intimate relationships, listening without preparing a counterattack is a form of discipline. It is also the ground from which giving and forgiving can actually occur rather than being demanded.

Sexuality, intimacy, and being seen

Sex is often treated as either a performance metric or a problem to solve. Existentially, it’s more revealing than that. Sexuality is one of the places where desire, vulnerability, embodiment, and shame converge.

In clinical work, I try to approach this without pathologising. Not “what’s wrong with you,” but: what does closeness evoke in you? what does being wanted mean? what does it cost you to be seen?

Because intimacy at depth is not a technique. It’s a willingness: to be present, less defended, more real. That is the part people fear -and the part they often want most.

The most generous expectation

Here is the unromantic truth that tends to help: a meaningful portion of your time together will be difficult. Not because you chose incorrectly, but because two imperfect people are trying to build a shared life inside ordinary stress: money, tiredness, misunderstandings, old wounds, recurring irritations.

Gottman’s research suggests many conflicts are perpetual -they don’t disappear, they get managed. The couples who last are not the ones who eliminate friction. They are the ones who learn repair: how to come back after rupture, how to soften rather than escalate, how to return without keeping score.

Expecting difficulty -rather than expecting permanent ease can be an act of care. It means you chose the person inside reality, not inside fantasy.

Choosing to stay

The aim of therapy (individual or relational) is not harmony. It is authentic connection: the capacity to face what is true, to name what is happening, and to choose with open eyes.

If any of this feels familiar — if you recognise your patterns but can’t loosen them, if the questions feel clear but the answers feel stuck — therapy can hold the work: not to “fix” a person, but to bring awareness to what has been operating in the dark, and to expand choice.

My version of Ya pihi irakema isn’t contamination as a romantic accident. It is this: seeing the whole picture — the inherited patterns, the permanent imperfections, the places you both become hard to love and choosing, deliberately and repeatedly, to stay.

As Erich Fromm wrote: “Love isn’t something natural… It isn’t a feeling, it is a practice.”

That is the kind of love I trust. And the kind I help people build.